Continuing our series taking a deep-dive into digitisation, today we get down to the nuts and bolts of digitisation and map out the processes involved in the ESA Archives, discovering each of the steps along the way and taking a behind-the-scenes look at our digitsation challenges!

As we noted in our previous article, digitisation is much more than the creation of a digital facsimile of an physical object. Even when taking on board the need for the digitised file to include complete metadata, only one of the four stages that we outline below actually deals with this part. So what else is involved and why is it not that simple?

Preparation

Archival holdings are organised and classified according to a hierarchy that runs from fonds to item (via sub-fonds, series and sub-series), with fonds being the entire collection and item being the smallest archival unit, for example an individual letter or photograph.

The first step in any digitisation project is to outline the scope of the proposed digitisation work and draw up a list of the material to be digitised. This overarching plan will then be broken down into different phases, each with various consignments made by selecting various series of material. In the European Centre for Space Records, for example, a series is often related to a project (such as Envisat or Rosetta) or to an administrative function (e.g Director General).

Once the selection has been agreed, a package needs to be put together for our partners who care of the digitisation, consisting of the series arranged in boxes and an accompanying list.

Collection in boxes

Within any series, files are the basic archival unit. A file is a group of information – in archival terms an organised unit of documents - put together by a creator according to a logical framework. This will often be because they relate to the same subject or activity, for example a group of contract files for a project, arranged in a chronological order.

These files are prepared in boxes with an individual ID and a separator (piece of paper) between each of them. Each analogue file will therefore become one digital file.

List

The files are accompanied by a list with all the metadata that can be provided in advance of digitisation. This would normally include the ID, title, date, period, creator of file or folder, size, any special details to note, including any previous publication.

The list is rarely created from scratch and is usually imported from other systems (such as the DMS document management tool used across ESA projects to manage information from the 1980s onwards) and completed by the ECSR using Dublin Core and ISAD metadata.

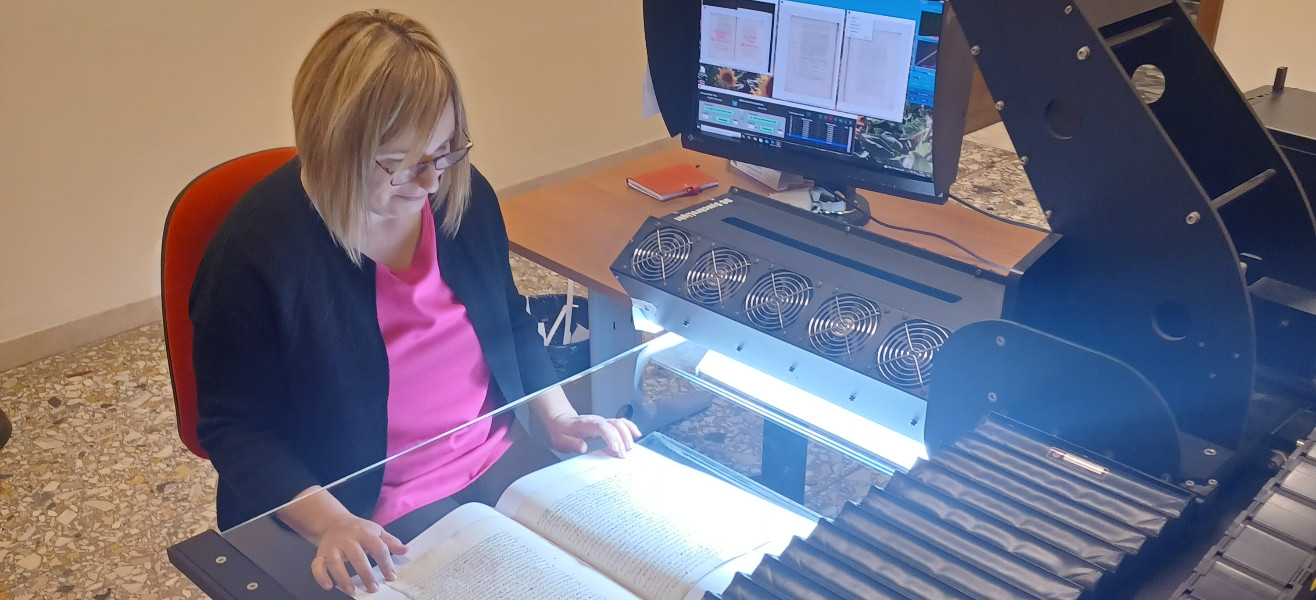

Digitisation

This is the heart of the process, when the material is scanned and where the digital files are created by unifying the scanned images with the metadata. But even here, it’s not just a case of running documents through a scanner, since our digitisation partners will be dealing with material in different formats, each of which might require a different approach, or use of different equipment.

Large drawings, for example, and formats such as microforms, may need to be scanned using special equipment, and decisions should be made on whether special formats are scanned as images or documents. (The quality desired for the end result also feeds into this decision-making process.)

The nature of the ECSR’s holdings also creates particular challenges: there is no unique template for documentation, with the sole exception of the official documents for meetings of ESA Council and its subordinate bodies, whose design dates back to the creation of ESRO in 1960s!

Additionally, ESA publications were often printed by different providers at different times. While small differences in margin width between two successive year’s Annual Reports may not be apparent when consulting the hard copies, they can be much more perceptible to the eye in digitised copies. And sometimes, things that appear to be a digitisation error – such as missing letters in a word in a handwritten document – are actually elements of the analogue original. In this example, due to a fountain pen running out of ink.

We asked our partners about the issues they encountered digitising our latest collections and they told us they had a wealth of examples!

“We often have to make judgement calls on what do with original material that is damaged or altered in some way (for example, when sheets that used to be glued together have become detached) or with mis-aligned prints. For prints, sometimes we can make manual adjustments such as rotation to rectify. In other cases, we scan the images as they are. This was the approach we adopted for the collection of ERS satellite images. It means that the digitised files will reflect any alignment issues and will include things like black masking tape covering part of the prints. It also means that we scan all the physical originals, including any duplicate prints.

We also sometimes find that the list of files does not match the material in the transport boxes - we then have to find what is missing and work out how to proceed.”

With this in mind, it is also crucial to have confidence in our partners and their professional abilities.

Ingestion

When the boxes come back to the ECSR, the first step is to unpack them and put the contents back into their location in the physical stack. As a general rule, we do not destroy original items after digisitation: because we can never know what people may wish to consult in our collections in the future and in line with the concept of cultural heritage as collections of authentic objects (both physical and digital) which each need to be preserved. We will have more time to explore ideas about the value of paper originals in a future article.

In addition to the boxes, an external hard drive will be included, with the original digital files and metadata. It is now over to colleagues in the ECSR team to ingest the contents of this drive into the ECSR’s archival systems and database. During this process, a node path (which acts in a similar way to a file path), specified by the digitisation team in the metadata, is read by the system which then directs the file to the right place in the archival database.

Curation (access control)

Once the files have been ingested into the system, their contents need to be carefully checked by the ECSR prior to deciding how and when to open them. On its conclusion, most archives adopt a similar approach the ECSR and release material at different levels of access, differentiating, for example, between in-house users and material open publicly.

How long does all this take?

In terms of the timescale, it can take up to six months to follow this process from the initial selection of a series to the final curation of the digitised files. With that in mind, it is perhaps now easier to understand why we so often refer to ‘ongoing digitisation activities’!

What happens next with digitised material?

Next up in this series, we talk to colleagues in international cultural heritage about the future of digital preservation: find out how the latest technology can be harnessed for sustainable access and enhanced research opportunities.