Our current series of discussions on digitisation now switches its focus towards digital preservation and on the development of cutting-edge technology for the future. Today we highlight the International Image Interoperability Framework – IIIF - and explore the opportunities that interoperability opens up for the exchange of information and for tomorrow’s scholarship.

While we will outline what IIIF is and how it came about, we have made a deliberate decision to not focus on how it works, but rather on why so many institutions are investing in it as a tool for access, community collaboration and research. (There is a wealth of online resources produced by the international IIIF community for digging deeper into how to use IIIF for your own research – we highlight just some of these below.)

What is IIIF?

The term interoperability refers to the ability of systems to exchange information with one another. IIIF is a set of open standards for delivering digital objects online to facilitate interoperability: it does this by making these objects work in a consistent way, that enables portability across viewers and the possibility to connect and unite materials across institutional boundaries. The IIIF specifications align with web standards that define how browsers work to enable richer functionality beyond viewing images: for example, to allow deep zoom, comparison, annotation and examination of structure (for documents, structure equates to page order).

IIIF is also an international community, backed by a consortium of leading international cultural institutions. In this spirit of collaboration, we contacted our colleagues across Rome in the Vatican Library, who are involved in this partnership, to find out more and to ask what this all means in simple terms for non-specialists!

The background to interoperability

Dr Paola Manoni is Head of Coordination of IT Services for the Vatican Library. She explained to us that the origins of IIIF can be found over a decade ago, against the backdrop of the many digitisation projects taking place in universities, museums, libraries and archives. A group of experts from some of these cultural heritage institutions got together and began talking about the feasibility of creating a unique environment to access digital resources that were held in different physical repositories. Their concept was not an enormous shared cloud, nor for a common way of managing digital objects, but for a way of unlocking interaction between these different servers, with the aim of making research in these collections easier for their end users.

The idea was that this common environment would provide a space for researchers to study different holdings, without the need to browse material in different physical locations or on different physical websites. The question of how to achieve this with the IT infrastructure available at the time was resolved with a technique using APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) to interact between different systems, an innovation led by IIIF.

As a result, researchers today can use any IIIF compliant viewer (such as the Mirador viewer in the ESA Archives’ SHIP database) to call up and put together digital objects using the name of the object - its URI (Unique Resource Identifier) - which in IIIF is known as the manifest.

IIIF is a versatile tool with other capabilities as well, and Dr Manoni outlined for us some of its key elements:

- unlocking interaction and access

- avoiding duplication in data acquisition and multiple copies of information

- standardisation of the method for calling images and accessing metadata

- revolutionising the concept of a digital object, unifying the object itself (such as a photograph) with all the information pertaining to it, including metadata, content and knowledge

We’ll take a closer look now at some of these.

IIIF for sustainable access

What do we mean by sustainable access? Put simply, it means that information becomes available and remains accessible. There are many facets to this, including making it findable, readable and future proof. A real-life example could be ensuring that information stays accessible beyond the lifetime of the individual digitisation project through which it was created, and the associated funding for the project website.

The capability that image interoperability opens us for re-use of digital objects is a powerful tool for access, with IIIF allowing users to create derivative objects with a new manifest. As an example, if a researcher has access to the manifests for three different digital objects (each a book), they can create another manifest describing just those pages that are of interest to them – such as page 10 of book one, pages 3-5 of book two and page 19 of book three. In this way, they have prepared and distributed through the web another manifest with information from other IIIF-compliant objects.

Reconceptualising research with IIIF

The revolution Dr Manoni mentions above involves a shift in research practice, from navigating different institutional sites to making use of an IIIF-compatible viewer as a workspace: users can bring documents from different web sources together to compare or cross-reference them at full resolution (without needing to download them) and add personalised content to their own copies. IIIF offers the digital equivalent to adding notes or highlighting relevant content by using annotations, which can also include tags, bibliographic references, citations, links to external URLs and multimedia content. In this way, researchers can unite the digital file, metadata and associated information, contributing to new ways of thinking about scholarship and digital objects.

One practical application of this is gathering IIIF images together into projects, or digital exhibitions without needing special technical skills or software. It also means that materials that belong together from different library, museum or archive collections, such as the output of a particular writer or artist, can be reunited.

This can all be done without in any way changing the original files, since creating an annotation adds a separate layer (or canvas) to the file, which can either be shared or kept private. (The best analogy that we found in our discussions was that of tracing paper as this extra layer!)

And beyond its advantages for individual scholarship, IIIF’s interoperable software offers research organisations a solution to the challenges of access to materials held across institutional silos, regardless of the backend server. Use of these digital resources can also be tracked across various platforms, providing a more complete view of institutional impact.

IIIF and the ESA Archives

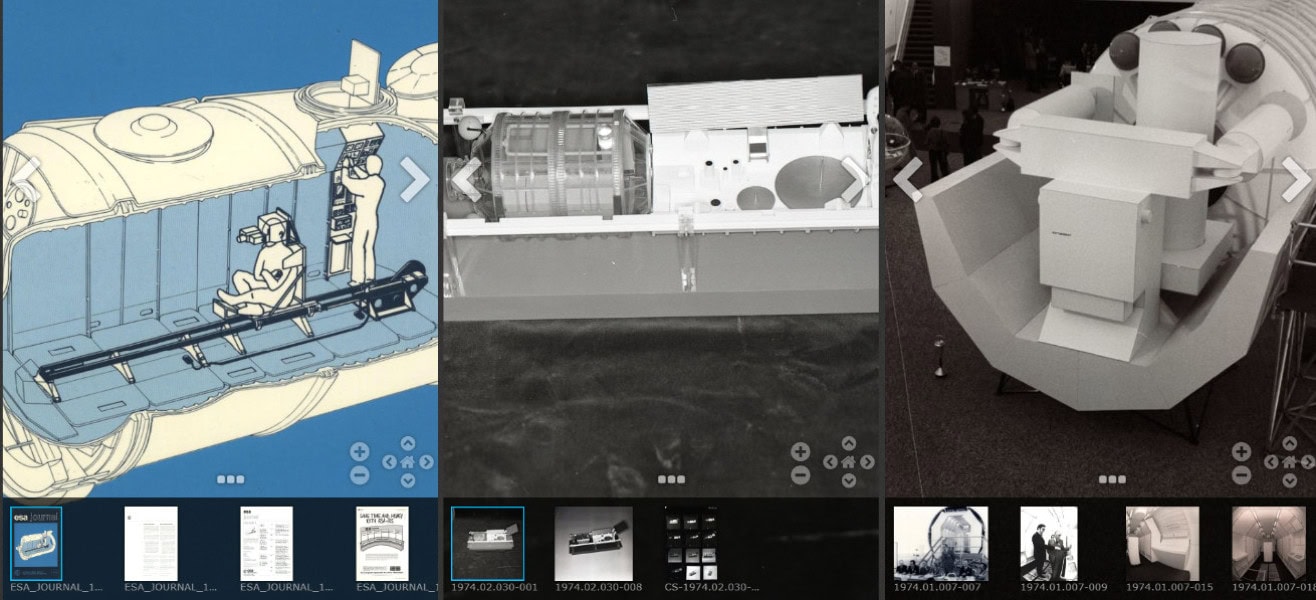

ESA is one of the first space agencies using IIIF, integrated into the Archives’ SHIP database.

Below each Series item thumbnail, a ‘Copy IIIF manifest button’ allows you to copy the manifest URL. This URL can be used in any IIIF compliant viewer, or SHIP’s built-in Mirador viewer, either to display the whole series or to compare images from different series or external sources. And on top of this, you can also add your annotations to these images in SHIP.

Understanding the concepts and potential of IIIF can be a challenge, especially if you are new to it. However, you can find many helpful resources, guides and training materials on IIIF’s dedicated website:

- plain-language guide for newcomers

- glossary of key concepts

- demos of IIIF

- IIIF YouTube channel

Next up:

Continuing our discussions on digital preservation, we will be turning a spotlight on sustainability and preservation, looking at how a file format developed for astronomical data can be used for long-term preservation, protecting digital collections for centuries against obsolescence and attack.